From the mainstream press, progressives, and the broader reality-based community, most analysis centered on how the pledge, and the individual woman chosen to fulfill that pledge, would help or hurt Biden’s electoral chances.

In both cases, it is presumed that the Biden campaign is making a calculation, reaching the conclusion that a commitment to putting a woman on the ticket will, the the aggregate, help his cause. Folks on the right, obviously, purport to know that it is a miscalculation and also somehow discriminatory against poor, poor men. Everyone else, more or less, has focused on the particular factors that motivated the pledge.

You know them already: Perhaps the campaign is seeking to give a jolt to turnout from women, who favor Democrats; they hope to attract women who may have voted for Trump in 2016 to switch sides at the prospect of electing a woman vice-president; they see a commitment to diversity as something that will unify and energize more left-leaning voters who may not feel great enthusiasm for Biden; it is intended to present to the entire electorate a glaring contrast with Donald Trump, who is known for—and even celebrates—his abuse and dehumanization of women. And so on.

In all cases, the analysis—be it negative, positive, or neutral—is about tactics. It is taken as given that Joe Biden made this pledge to help him win the presidency, and all that’s left to do is to qualify and quantify that choice.

I am no grizzled veteran of national political wars, but I have been working in various arenas of national politics for 13 years, including a presidential campaign, and I can tell you with certainty that yes, this pledge was made after weighing all of these tactical factors. But I also do not believe they were decisive. Because what I also can tell you from my experience is that all of the people involved in these mammoth and byzantine political enterprises are human beings.

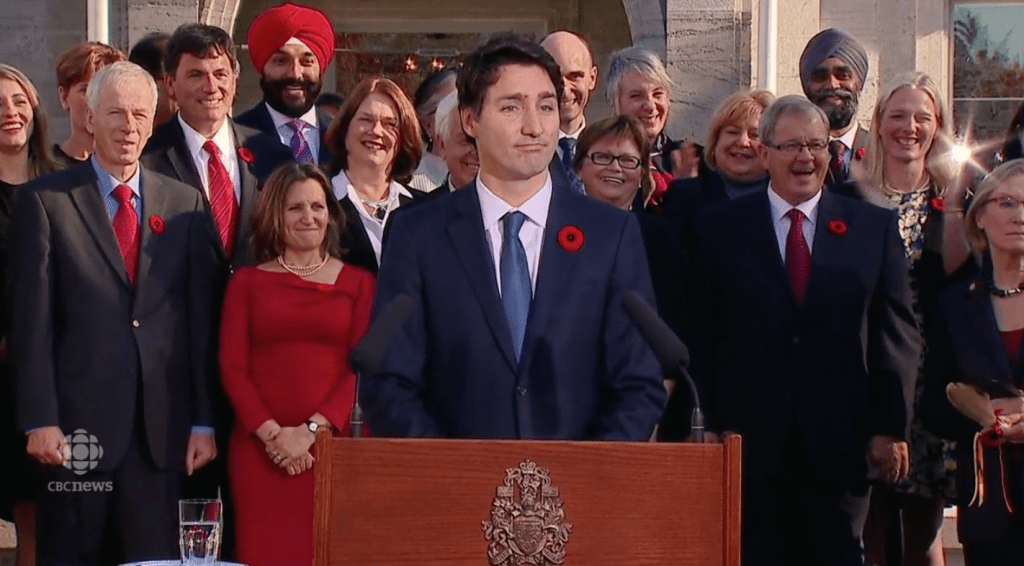

Let’s take a trip way back in time to another era, one that might be unrecognizable today. Hop in our time machine and we’ll set the dial back five whole years, and we’ll set ourselves down in the city of Ottawa in a magical land called Canada.

Standing at a podium before the national press was an impossibly handsome new prime minister, Justin Trudeau, flanked by his newly-appointed cabinet. True to a pledge of his own, Trudeau had assembled a cabinet with 15 men and 15 women.

“Your cabinet, you said, looks a lot like Canada,” said one reporter. “I understand one of the priorities for you was to have a cabinet that was gender balanced. Why was that so important to you?”

There is a pause, during which Trudeau somehow manages to simeltaneously deadpan and smolder, as only he can. He responds.

“Because it’s 2015.”

And then he gently shrugs.

Trudeau went on to explain that he had chosen excellent people for an excellent cabinet that represented the country’s diversity of viewpoints, but mentioned not one more word about anyone’s gender.

Those who worry about “tokenism” claim to be concerned at the great injustice done to better-qualified candidates for positions being rebuffed for lesser-qualified choices who tick an identity checkbox. But this makes the absurd assumption that there is always one, single “best person” for any given job, one “right answer” among a sea of wrongs. It’s preposterous.

For any position there exists a wide variety of individuals who might excel, bringing to bear their own unique blend of skills and experiences. The idea that there’s a singular “best person for the job” is a trope, an ideal to which one can aspire, but not some incontrovertible mathematical constant. We’re talking about human beings working within human-created systems.

Trudeau’s unspoken message was that he had indeed chosen the “best” people for their respective cabinet positions, and that there were any number of “best people” he might have chosen. For the project of appointing a national cabinet, achieving a gender balance was no hindrance. Trudeau was telling us that because of the wealth of talent available to him, there were no compromises or consolations in ensuring gender parity.

And by saying, “Because it’s 2015,” he was really saying, “Because it’s the right thing to do.”

In the Biden campaign’s decision to publicly commit to placing a woman on the ticket, there is no doubt that many surveys were studied, many polls were taken, many consultants were consulted, and the political temperature of many constituencies was taken. This is presidential politics, and politics must be done.

Joe Biden is also a human being. He leads a campaign made up of human beings. All of them got into politics and government for a reason, and I’m willing to hazard the guess that the vast majority of them did so for the right reasons, imperfect as they all are. And as imperfect as he is, I think Joe Biden is in politics for the right reasons.

At the March 15 debate on CNN in which this pledge was announced, Biden channeled a bit of Trudeau (though, he could never come close to Trudeau’s unflappable delivery). “My cabinet, my administration will look like the country and I commit that I will, in fact, appoint a — I’d pick a woman to be vice president,” said Biden. “There are a number of women who are qualified to be president tomorrow. I would pick a woman to be my vice president.”

In other words, to commit to choosing a woman is in no way a limitation. There are myriad women, right now, who would be excellent presidents, and he’s going to pick one of them.

I can’t know anything for sure about what’s in a man’s heart, but I think Joe Biden has committed to running alongside a woman because he thinks it’s the right thing to do.

Because it’s 2020.