It’s the late autumn of 2017, and I’m in Point Reyes Station, California for a two-week writers’ retreat. I was walking down a remote road, taking one of my regular strolls into town for supplies, a bit of exercise, and to take in the landscape, which was stunningly beautiful. The weather was nearly perfect, and being so removed from everything, cars and other pedestrians on the road were quite rare. I was alone and enjoying the movement and the environment.

The wind picked up a little and it whooshed deeply in my ears. You know the sound, the low thup-thup as the air pummels your earlobes. Maybe I hear it more than others because my ears are little on the bigger side, so they scoop up a bit more air.

Only something was off. The whooshing sound was there, but it was only coming in on the right side of my head. That was weird. I must have just happened to be facing in such a direction that the wind was hitting my head at that particular angle. So I checked.

I pivoted my head in different directions, while walking, while standing still, and nothing changed. I walked to different parts of the road with different landscape features; fewer trees, fewer houses, atop an incline, then toward the bottom. Still the same. I wasn’t hearing the wind in my right ear at all.

I snapped my fingers in both ears, and noticed no meaningful difference. I rubbed my finger along the surface of my earlobes and ear canals. In the left ear, I could hear the deep rubbing and rumbling sounds of the friction. In my right ear, I heard a faint and wispier sound, like something soft brushing on paper, at a distance.

I got out my headphones and attached them to my phone. I played some songs, and only listened through one earbud at a time. In the left ear, the full, rich sound came through that I had come to expect and enjoy from this particular pair of headphones. In my right, the bass and mids were, alarmingly, almost nonexistent, save for the high-frequency sounds of strings being scratched or plucked. All I heard were higher-end sounds, such as vocals, snares, and cymbals, only much tinnier, thinner, weaker.

Finally, I tried listening to a voicemail to see if I could hear a phone call. Again, the expected normal sound of the voice came through the phone’s little speaker into my left ear. Putting the phone up to my right ear, the voice sounded like it was coming from a tin can stuffed with cotton. I could hear the voice, but barely.

This was unmistakable. I wasn’t being paranoid. I had lost hearing in my right ear.

*

It’s the spring of 1994 in Absecon, New Jersey. I’m a 16-year-old junior in high school, in an exurban basement. It’s the house of one of my friends from marching band, Chris, and by way of some now-forgotten confluence of agreements and compromises, I have formed a crappy little band with him and two other friends; Chris on drums (talented thrash metal devotee), my best friend Rob on bass (had never played, and was borrowing my dad’s sort-of vintage bass guitar), me on lead guitar (I had no business being a lead guitarist but I could play chords and learn songs by ear relatively easily), and one guy I met through Chris, Corey, our lead vocalist, a kind of Axl Rose/grunge type (and who was tone deaf).

I told you it was a crappy band.

Nonetheless, it was my band, and my sole outlet for playing with a full set of musicians on a few songs I really liked (and some I really didn’t, but like I said, agreements and compromises). In the year or so we played together, I don’t know that we ever got to the point of being “good,” but we did manage to scrape together a handful of songs that we could enjoyably hack our way through. It was fun, at least some of the time.

On this occasion, we’ve been a band for a few months, and Corey and Chris have brought with them a friend of theirs, another guitarist who was straight from the Metallica/Megadeth school of metal. He had the requisite long hair and patchy teenage facial hair, including that mustache so many of those guys wore back then that usually signaled to me, for some reason, that I should be wary of them. I don’t remember his name, so let’s just call him “Patchy-stache.”

Apart from having some obviously advanced skills in metal lead guitar, Patchy-stache also brought with him something else we didn’t have: a giant-ass stack of huge amplifiers. For our usual rehearsals, I hauled back and forth my dad’s ancient Vox tube amp and a very small beginner’s amp that I’d gotten as a birthday present. Corey had a decent amp and PA for his vocals and occasional guitar playing. With what we had, we could barely hear ourselves over the astounding pound of Chris’s drums. That guy did not mess around behind that set. Usually I wore earplugs to protect my hearing, though not always. I was afraid it made me seem like a wuss.

So here we were in this small space, enclosed in concrete, with our usual collection of aspirationally loud shit. And now here’s Patchy-stache with his menacing obelisk. When he played through it, the obelisk emitted these teeth-rattling, piercing riffs, filled with stabbing licks and needle-like harmonics. It was painful. I of course didn’t know at the time that I was autistic, and already wired to be overwhelmed by stimuli like noise, and I didn’t have my earplugs in.

But I dared not show my discomfort. Checking for the other guys’ responses to this sonic assault, they seemed totally unfazed. I tried to indicate that this decibel level might be a bit too much with some humorous gesticulations of my ears exploding. It got me some smirks, but nothing else. It was really quite awful, but if there was one thing I found more excruciating than a storm of stimuli, it was the threat of social rejection, of being called out as lesser than the others. So I endured.

That night, I of course had ringing in my ears, like anyone would after a loud concert or something. But in addition to the ringing, there was also a low humming sound in my right ear, which happened to be the ear that was more directly facing Patchy-stache’s amps. It had clearly taken the brunt of the abuse.

The next day, the ringing had left both of my ears, but the hum remained. And it stayed. Forever.

*

I got used to it. At first it drove me nuts, and I had trouble sleeping. But I think it was only a few months before I’d learned to manage it. When there was sufficient ambient sound, the humming almost “turned off.” It weirdly just seemed to stop when there was enough sound around, not just fade to the background to become less noticeable. Whether that’s true or not is kind of academic, since tinnitus (the name of the condition) is mostly about the brain responding to a trauma. It’s a kind of illusion, but also not.

I’d learned to sleep by having music on at night, and that became a years-long habit regardless of my tinnitus. Throughout high school and college, most of my music listening happened in bed, where I’d fantasize scenarios in which I and my friends, all of us now musical virtuosos, were the ones performing these songs. I loved those fantasies. Now they just hurt, but explaining that is for another time.

Going into full adulthood (assuming I have actually done that), the hum became a total non-issue. It was always there, and I was aware of it, but it no longer troubled me at all. It was just part of the sound of being alive.

The right ear remained sensitive, however, so I’d shrink from blasts of sound directed at it. I’d had a few scares after, say, acting partners or overexcited children would inadvertently scream in my ear, causing me acute physical pain, but it always subsided and things went back to normal. And if the stabbing that Patchy-stache’s amps perpetrated on my ear had reduced my hearing at all, I couldn’t tell. For over two decades, I enjoyed the full scope of stereo sound, and as far as I could perceive, heard equally well out of both ears.

I didn’t appreciate it like I should have.

*

It’s the early autumn of 2017, a few weeks before I’d go to the writers’ retreat in California. My sinuses feel a little plugged up, which is not at all unusual for me. The usual pressure, the usual feeling of crud in the back of the throat, but it’s all very mild. I don’t even really notice it.

What I do notice one evening is my tinnitus. As I said, I have a baseline awareness of it as a matter of course, but I don’t often “notice” it. Well, now I did, a lot. The subtle hum was now blaring in my ear, several orders of magnitude louder than usual. Though this was unpleasant, it wasn’t totally surprising. Once every long while, some nasal or sinus related thing will make it sound a little more present in my head, and it always passes, returning to normal.

But jeez, this was really quite loud.

Days went by, and it wasn’t getting any better. If anything, it was getting worse. The sound was even louder, producing a sensation that was kind of like something pressing against my face. It felt like I had my head flat up against a some sort of enormous air compressor, subtly pushing into me. Or like the hum of all the electricity in the world was behind a wall to which my ear had been affixed with superglue.

My doctor said it was probably just a sinus infection affecting the existing tinnitus, and that would hopefully clear up with some antibiotics and decongestant. This felt particularly urgent, given that I was about to head off to California for my fortnight of writing. The last thing I wanted while trying to enjoy the peace of staring out over the San Andreas fault was to have the sublime state constantly interrupted by the jet engine in my head.

Unfortunately, by the time of my trip, the problem still persisted. The sinus treatment had no effect. I had some hope that maybe the shifting air pressure of my upcoming flights might sort of pop the problem out. But, of course, no. So I just had to cope.

A few days in, I noticed that I couldn’t hear the wind in my ear. A couple of days after that, the sound amplified yet again, out of nowhere, to the point that it physically hurt, causing me to experience a little vertigo. I saw a doctor in town and was prescribed some ear drops as a kind of shot in the dark, which also did not help.

Shortly after my return home, I saw a couple of specialists and had my brain scanned. The audiologist was the only one with any news, and it was not really news. I had indeed lost much of my ability to hear the low and middle frequencies of the sound spectrum in my right ear, and the tinnitus was my brain’s misguided attempt to investigate and compensate for the loss. Because they were happening at the level of the brain and inner ear, both were almost certainly permanent.

Both are permanent.

*

I have lost very little, really. I’m not by any means disabled. I’m not even a good candidate for a hearing aid. Someone whose pinky was cut off in an accident will struggle far more with their loss than I will have to with mine. With all the things that a human could suffer, with all the debilitating diseases, injuries, and accidents of fate that could befall a body, this doesn’t even approach the status of “big deal.”

But it’s still a loss, isn’t it? A little one. And sometimes little things matter a whole lot.

There is a space in the constellation of sound that one of my ears won’t ever experience again, not meaningfully. It’s just gone.

When I’m working on a recording for one of my songs, I’ll no longer be able to rely on my own senses to find the right blends and mixes of sounds that will bring the music to life. One side of my head will be missing way too much of it. It would be like directing a play with the lights dimmed on half the stage.

(I guess I could produce everything in mono. I mean, the Beatles did for a while.)

The other ear is fine. The full sonic palette remains available to it. But both ears, of course, will now only get worse as I age, because that’s what happens to human bodies. More colors will dry up or be scrubbed off my palette.

And then there’s the hum. Or rather, the droning. That’s a new reality that must be accepted as well. I became so accustomed to its first manifestation over the past 23 years, that I had the luxury of giving it almost no thought at all.

Now it’s a different story. This new, louder sound is always there. Even when I’m distracted by other sounds, ambient or otherwise, I remain aware of the droning. And because it pulses erratically in tone and intensity, it’s as though it’s not satisfied to merely exist. It’s like it wants my attention. It wants me to feel menaced by it.

It might yet become tolerable or even of negligible concern as the years go by. I kind of doubt it.

But I’m fine. As far as da-to-day obstacles, the hearing loss just means I’ll have to say “what?” more often, which will at times get a little frustrating for me and the people around me, and that’s really nothing. The droning, well, that will bother me exclusively.

Regardless of the relative severity (or lack thereof) of the loss, I’m grieving it. I’m sad and angry about the fact that I’ll never experience music and sound to the full, rich extent that I once did. That I so loved. That filled me up and saved me. Most of it is still there, but it will never be the same again. And I’m going to mourn that.

Please consider supporting my work through Patreon.

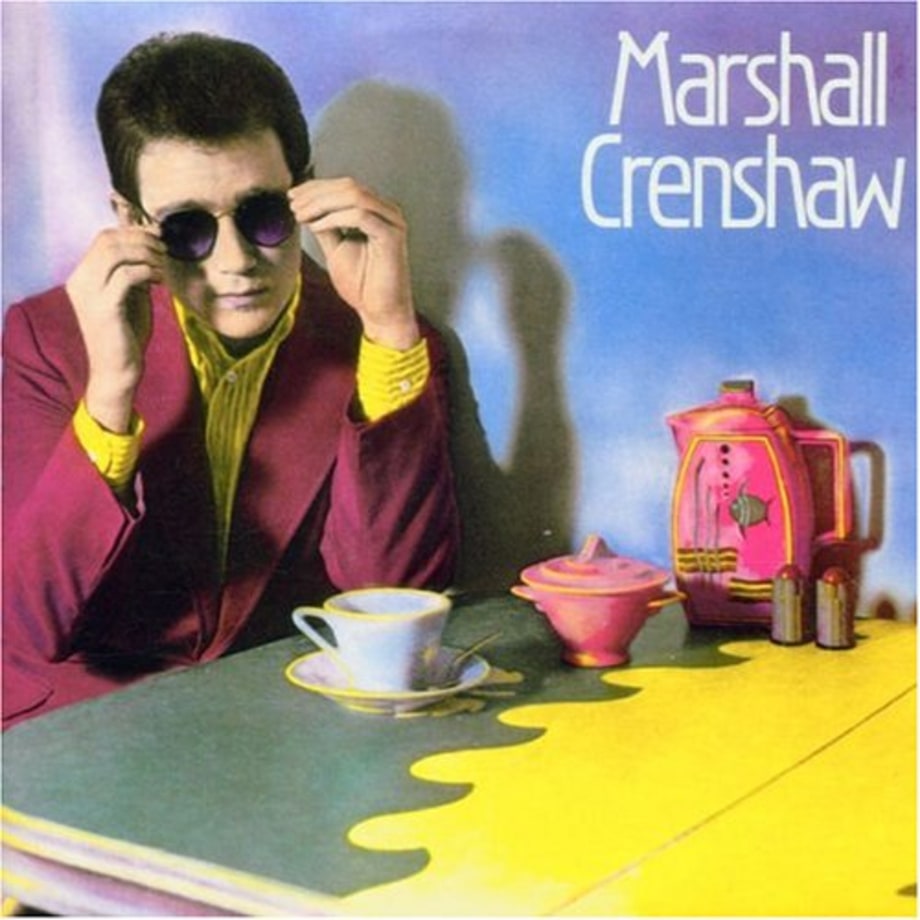

I was very close to never having heard of Marshall Crenshaw. It just so happened that my dad had used a cassette copy of

I was very close to never having heard of Marshall Crenshaw. It just so happened that my dad had used a cassette copy of